Sunset over Lake Tanganyika at Kalemie, in North Katanga. Under Mobutu, this province's mineral resources and mining industry used to generate over 50% of the country's GNP. Now it festers in a state of aggrieved destitution while its political and sundry military leaders engage in willful self-mutilation. Kalemie itself, suprisingly, is calm and I walk around at night without fear. But the province is at least 2-3 years behind the rest of the country in terms of the peace process; disarmament and demobilization of military factions has barely begun. An excellent overview of the dysfunction in this particular corner of the country can be found here.

I am here with a team of evaluators to assess the impact of a number of internationally-funded projects to secure the release of child soldiers from an array of military groups and to return them to their families and communities. If the projects are successful, the children will return with the means and mental wherewithall to resist the pressures of re-recruitment, as combat continues and children make the best soldiers--so the logic runs--because they rarely disobey or run away, they dont require a salary and their minds are perfectly malleable, unlike adults and older adolescents.

Such evaluations are always exhausting, and this one is no exception. Today is Sunday but we have much planned: a motorcycle trip out to a village where a number of children have been reunited with their families after being released by some of military groups still active around here. We tried to get there yesterday by jeep but the mud was endless and we had to return to town. Instead we visited a local transit center for recently released children, who await reunification with their families, provided these latter can be found. The boys we met there were mostly under ten. Prepubescent kids serve mostly ritualistic roles and rarely bear arms. Those we met were used to transport the fetishes and various magic effects around for Mai Mai militias (who believe, for ex., that their bodies are bullet proof). Pre-pubescent girls are made to wash the naked bodies of the adult combatants with magic potions before and after battle. Many such girls are daughters of the Mai Mai officers and commanders, so any prospect of securing their release from military servitude is scant.

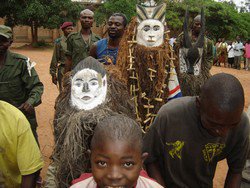

Mayi Mayi and soldiers dance together

at Dubie, Katanga. Credit: UNICEF

Older kids serve as spies, porters or are sent to the front as cannon fodder. By the time we meet them in these transit centers they are often traumatized with extreme ADD. They are aggressive at first, sometimes fighting amongst themselves or banding together to smash windows and break furniture at the transit center. In some centers we've visited, children have taken their caretakers hostage, demanding money, goods or immediate release. Rape of younger boys by older ones is sometimes reported by staff; children re-enact the brutal heirarchies of their former military existence because it is more familiar to them than civilian or family life.

Older kids serve as spies, porters or are sent to the front as cannon fodder. By the time we meet them in these transit centers they are often traumatized with extreme ADD. They are aggressive at first, sometimes fighting amongst themselves or banding together to smash windows and break furniture at the transit center. In some centers we've visited, children have taken their caretakers hostage, demanding money, goods or immediate release. Rape of younger boys by older ones is sometimes reported by staff; children re-enact the brutal heirarchies of their former military existence because it is more familiar to them than civilian or family life.While aid workers trace and contact the children's families to prepare the process of reunification, the hard work of 'demilitarizing' their minds gets underway. Once found, preparing the family and community to accept the child's return is compounded by the difficulty of finding the kids something constructive to do that might generate a meagre income -- largely impossible in war ravaged areas where there is no local economy. There is rarely money in circulation, nor is there anything to buy or sell. Bartering for basic foodstuffs is the norm in rural areas. Like everywhere else in the country, there are few medical facilities, drugs or trained staff, so if a child gets diahrrea or a fever s/he will likely die.

In such an economic desert, once released from the militias and back in their villages, former child soldiers quickly get restless and frustrated. Large numbers voluntarily return to military life for want of something to do and the possibility of partaking in the spoils of war, usually little more than ransacking the neighbors, who have nothing anyway.

When I meet these kids I often think of my nephew, who is their age. They enjoy speaking with a foreigner in Lingala, the language used by many military groups, even here in Swahili country. But their minds are in a very different place: partly fried, partly deformed by combat and the 'Lord of the Flies' reality that has been theirs for years, in some cases. In others I can sense an inner child still present but lost or clouded by memories and military conditioning. Many have the incongruous air of adult combatants with their unpredictable moods that swerve erratically between vacant, mile-long stares to hostile agitation, triggered by the sound of a voice or the sight of a foreigner.

The programs we are here to evaluate are confronted with enormous challenges, and their chances of sustainable succes are slim due to factors beyond their control -- nothing in this environment is conducive to normal childhood, or normal life for that matter. We have about 2 weeks left and many many more projects to visit, scattered all over the country, wherever militias, rebel factions or the government army itself have been using child soldiers.