In an excellent editorial by, I'm assuming, Sebastian Mallaby in this morning's Washington Post, the obstacles facing the much debated and awaited UN re-hatting of AU peacekeepers in Darfur are laid bare. People unfamiliar with the internal politics and divergent loyalties of Security Council Member states tend to blame the Darfur tragedy on 'Western inaction' or 'Khartoum intransigency'. Both are true, but amount to blaming today's weather on 'the weather' -- a finer tautology could not be found.

In an excellent editorial by, I'm assuming, Sebastian Mallaby in this morning's Washington Post, the obstacles facing the much debated and awaited UN re-hatting of AU peacekeepers in Darfur are laid bare. People unfamiliar with the internal politics and divergent loyalties of Security Council Member states tend to blame the Darfur tragedy on 'Western inaction' or 'Khartoum intransigency'. Both are true, but amount to blaming today's weather on 'the weather' -- a finer tautology could not be found.The resulting absence of a common front of decisive action on problems like Darfur or Rwanda is not justifiably glossed as 'the failure of the UN', as many would have it. It is simply the working reality of multilateral bodies where state interests dominate the agenda exactly as they do in the world of bilateral interaction between sovereign states. States act the same way alone as when they are in a team huddle; that is, they protect themselves and their friends of the moment. If we want UNSC member states to act differently, i.e., with greater common concern for problems like Darfur, someone needs to invent an entirely new basis on which states interact. Can the sheer force of human will stop dogs from randomly humping one another at the park? I think not; it is their nature.

UNSC Member states often have competing agendas, particularly when their interests converge with those of the offending government who is the subject of a pending Resolution, in this case Khartoum. China's oil interests in Sudan of course affect its position in deference to Sudan's wishes, as do the votes of other Arab countries, generally loathe to oppose publicly the actions, however murderous, of fellow Arab governments. Mallaby lays all this out clearly and definitively in his editorial. Sub-saharan African governments are often equally guilty of protecting their own, making the work of the AU all the more complex in any context, not just Darfur.

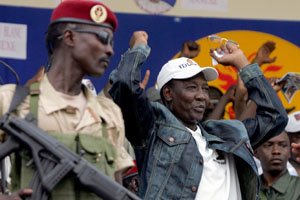

But he reserves his most lucid vituperation for President Bashir of Sudan, and the consistently arbitrary logic deployed to oppose international action on Darfur. UN peacekeepers are numerous across south Sudan to monitor the North-South peace agreement, but Bashir and other Arab nations oppose a UN intervention in Darfur, preferring an AU force that is far too weak and underfunded for the task. This is just face saving that facilitates the blood letting, and deserves all the scorn the world can muster. A full-on military intervention, in my opinion, would probably unleash another Somalia and perhaps an Iraq--a country with a far clearer record of Al-Quaeda connections than Iraq.

"Mr. Bashir has already accepted a 12,000-member U.N. force in Sudan's south, so he can't claim a principled objection to the presence of U.N. peacekeepers in his country. But he retains an unprincipled determination to keep the United Nations out of Darfur, even though the need for a peacekeeping force is clearer than ever.

The world needs to be clear what Mr. Bashir's position amounts to. As a result of his government's systematic destruction of African villages in Darfur, more than 2 million displaced people there depend on humanitarian relief, but mounting violence that claimed the lives of eight aid workers last month makes the delivery of relief extremely difficult. In these circumstances, barring the entry of peacekeepers is to condemn thousands of displaced civilians to starvation. It is to continue the policy of genocide that has marked this crisis from the outset."

African Union forces will be definitively broke by end September, and no nation is stepping forward to bankroll them further, as has happened at previous junctures of economic crisis for the few troops spread across Darfur.

Whether the pending UNSC Resolution is passed, and what it will stipulate (20,000 UN peacekeepers are the main menu item), will testify to the existence of a unified front on Sudan. Should it land flat and go nowhere, civilian survivors in Darfur can begin digging their own graves.