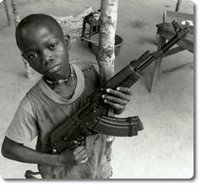

I was in Congo much of November 2005 to evaluate the success of various aid projects to 'support the political transition' at the community level. I will return this week to begin looking at international efforts to rehabilitate former child soldiers, or 'kadogos' as they're called in Congo. Congo's national elections will be soon upon us, after three years of largely unsatisfactory transitional government. What follows are some thoughts on how aid projects funded by the international community can engage this negative dynamic in support of a more promising transition, credible national elections in April and a serious start at legitimate governance for the victorious party.

I was in Congo much of November 2005 to evaluate the success of various aid projects to 'support the political transition' at the community level. I will return this week to begin looking at international efforts to rehabilitate former child soldiers, or 'kadogos' as they're called in Congo. Congo's national elections will be soon upon us, after three years of largely unsatisfactory transitional government. What follows are some thoughts on how aid projects funded by the international community can engage this negative dynamic in support of a more promising transition, credible national elections in April and a serious start at legitimate governance for the victorious party.In sum, disengagement and the self-interest of Congo’s political elites, combined with their mutual mistrust, has resulted in a dysfunctional transition; this political dysfunction is also a root cause of Congo’s material and social destitution. Nor is there a sufficiently robust civil society to act as a safeguard against excessive predation by the elites or even to mediate relations between the masses andgovernment officials. Congo’s ragtag civil society of NGOs and media outlets serves rather as means of economic survival for its adherents, rather than a tool to hold the state accountable.

In the shadow of Mobutu

Struggling to transition from dictatorship to democracy since its return to multiparty politics in April 1990 under Mobutu, Congo’s path to democracy remains extremely rocky. The basic democratic requirements of minimum state capacity, order, and disincentives to violence are totally absent. This is compounded by citizens’ distrust of political actors and manifest distrust among the actors themselves.

The Inter-Congolese Dialogue resulted in the adoption of a Transition Constitution and of the “Global and All-Inclusive Agreement on the Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” ratified in April 2003. These documents set up the principles and objectives of Congo’s transition, including reunification, pacification, reconstruction, restoration of territorial integrity and of state authority over this territory, the creation of an integrated army, and the organization of elections. This resulted in the formation in June 2003 of a Congolese power-sharing government composed of members designated by the delegations attending the Dialogue. The new government had a “1 + 4” formula at its core which reserved the presidency for Joseph Kabila (son of late Laurent-Désiré Kabila, assassinated in January 2001) and appointed four vice-presidents.[1]

[Kabila pere: Gone the way of Che]

Together with a 40-strong executive, a parliament of 620 appointed members, and several “institutions of support to democracy” (the Independent Electoral Commission, High Authority of the Media, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, and Human Rights National Observatory), the new government was charged with organizing the transition to democracy over a two-year period. Of particular importance also was the establishment of the International Committee for Accompaniment of the Transition (CIAT), composed of members of the UN Security Council, international donors, and some African governments, which was charged with protecting transition institutions and arbitrating disputes. The government was appointed on June 30, 2003, inaugurating a two-year transition period which included among other things: the adoption of a draft constitution; a law on the principles of nationality; an electoral law; registration of voters; a referendum on the draft constitution; and the election of a parliament and president.

Despite the presence of over 16,000 UN peacekeepers in country, ongoing violence across the eastern provinces underscores the fragile state of the transition. Armed groups of disparate allegiance have failed to commit to the peace process. This insecurity limits the geographic reach of aid agencies into key areas of vulnerability and dire need. Continued conflict and transition dysfunction have meant that by early 2005, Congo’s transitional government had yet to pacify or extend its authority across its territory. As a result, national elections were delayed by six months, provoking violent outbursts and insecurity from a desperate and impatient population.

[UN peacekeepers in the East]

The Congolese transition has been characterized by a high level of institutional dysfunction and a paucity of achievements. Although the government, parliament and military hierarchy were installed by September 2003, most of the “support institutions to democracy” took much longer to become operational, in part because of the government’s failure to adopt the necessary legal texts. The quest for personal enrichment by members of the various transition institutions has triggered widespread reciprocal suspicion among them has made it all but impossible to establish functional cooperation among the different organs of the state.

The Congolese transition has been characterized by a high level of institutional dysfunction and a paucity of achievements. Although the government, parliament and military hierarchy were installed by September 2003, most of the “support institutions to democracy” took much longer to become operational, in part because of the government’s failure to adopt the necessary legal texts. The quest for personal enrichment by members of the various transition institutions has triggered widespread reciprocal suspicion among them has made it all but impossible to establish functional cooperation among the different organs of the state.Given the huge discrepancy between what international aid agencies can deliver and the capacity of the state to participate and contribute in the country's reconstruction, it is understandable that communities see no ‘transition dividend’ from their government. Indeed, there remains a strong sense among Congolese that the transition is controlled by outside forces, its outcome foretold and beyond their control. This non-credulity undermines popular engagement and ownership of the transition process. [In fairness, this suspicion is somewhat justified: the CIAT, national elections, Inter-Congolese Dialogue and Sun City, MONUC peacekeepers, and DDR agencies – all of this is funded and driven by foreign actors.] Further, the conviction that the West profits from Congo’s chaos (via mineral extraction and arms sales) is widespread. There is relatively little sense that Congolese elites are the primary enablers of this resource theft.

A difficult dilemma preoccupies many Congolese today, that between a recognized need for outside intervention for a successful transition, and the common belief that outsiders control Congo and profit from its dysfunction. The result is a legitimacy deficit regarding foreign donors or international agencies, as well as Congo’s political elites. During my recent evaluation trip, I heard a common refrain: “Why vote for any of our officials; what have they done to earn our vote?”

[Joseph Kabila: former kadogo]

Many aid agencies seem to assume that the transition will succeed and the State will pick up and resume the work of stabilizing the country and rehabilitating essential public services. Unfortunately, this is not likely to happen, and the Congolese know it. Because so many aid operations avoid the messy work of directly involving state officials and transition institutions in their relief activities, the problem is compounded. International aid subsitutes for the work of the state, and thus risks triggering a legitimation crisis for the state -- not necessarily a bad thing if it could lead to better governance. What it usually leads to are militant crackdowns and more brazen theft of public funds and resources by political elites.

Many aid agencies seem to assume that the transition will succeed and the State will pick up and resume the work of stabilizing the country and rehabilitating essential public services. Unfortunately, this is not likely to happen, and the Congolese know it. Because so many aid operations avoid the messy work of directly involving state officials and transition institutions in their relief activities, the problem is compounded. International aid subsitutes for the work of the state, and thus risks triggering a legitimation crisis for the state -- not necessarily a bad thing if it could lead to better governance. What it usually leads to are militant crackdowns and more brazen theft of public funds and resources by political elites.In setting up and running their operations, very few aid agencies or bilateral relief efforts implicate government officials at the national or provincial levels. In so doing, aid groups step directly into the role of service provider, thereby allowing the transitional government to continue its infighting and introspection and to disengage from social service provision, including salaries for health and education workers. Ongoing neglect of the country’s basic needs fuels the popular sense of abandonment, thus furthering the government’s current legitimacy crisis in the eyes of citizens. Inclusion of local, provincial and national transition actors and institutions in community reconstruction work should be recognized as a core strategy for aid groups to advance and reinforce the transition.

One of the programs I was recently evaluating was of the 'community-focused reintegration' model, also used in Sierra Leone, Burundi and Liberia to re-weave the social fabric after a decade of mutual decimation, and to re-connect the population to the national political process. The CFR program I was visiting sought to support the political transition in DRC by strengthening participatory processes at the commumity level, in an effort to improve community self-reliance and self-determination. However, there was nothing for communities to work with. Dire poverty and a total absence of capital have spelled utter dependency for many rural communities. This was particularly true in Ituri , where conflict and displacement still prevent continuous farming. When enjoined to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, community members in Ituri responded: “We have no boots!” Moreover, the government’s incapacity to provide the bare minimum of services reinforces the sense of dependency on outside actors and foments discontent. Such frustrations are a potential source of post-election backlash, since the bouts of mass looting and vandalism over the last 15 years have been triggered by a similar sentiment and conditions.

[Kadogo: proud to serve]

The CFR program ‘opened minds’, or so many participants enthusiastically claimed. Political support and votes can no longer be bought, they told me; similarly, many youth claimed to be less susceptible to political manipulation and violence. When asked about national elections, they all responded: “What have these candidates done to earn our votes?” After nearly two years of this particular CFR program, worth millions of dollars, the behavior and instincts of the political class are unchanged; only voters have evolved. The common sentiment is that the poor are constantly subjected to bad governance, but are not given the means to change it. While this may constitute increased awareness of the political transition, it does not come with the desired component of popular empowerment.

The CFR program ‘opened minds’, or so many participants enthusiastically claimed. Political support and votes can no longer be bought, they told me; similarly, many youth claimed to be less susceptible to political manipulation and violence. When asked about national elections, they all responded: “What have these candidates done to earn our votes?” After nearly two years of this particular CFR program, worth millions of dollars, the behavior and instincts of the political class are unchanged; only voters have evolved. The common sentiment is that the poor are constantly subjected to bad governance, but are not given the means to change it. While this may constitute increased awareness of the political transition, it does not come with the desired component of popular empowerment.Transition, yes - but where to?

Over all, inept governance by transition actors and ongoing violence in the East are the ‘weakest links’ of the transition. Despite an easily foreseeable prolongation of the transition period (elections particularly), the US-funded agency I was evaluating showed no apparent willingness to shift its timeframe and budget to accommodate the delayed elections--they are ending operations in March 2006. Bypassing opportunities to engage the various transition support institutions and ‘commissions’ created by government, this and similar aid agencies forfeit a valuable means of reinforcing the transition by working with the political class at national level. This appears to be due to a ‘grassroots bias’ in many community-based aid programs, for the weakest link in the transition is the political elites, not the communities or ex-combatants. Such opportunities were lost, I argued, because of an unexamined assumption in the program design that communities are somehow more central to a successful transition than the politicians themselves.

In Congo today, there is no substrate for development: no infrastructure, no managerial or administrative systems of any kind; nor is there any human capacity to implement such a management system, public or private, at local or national level. If the administrative and political classes lack these basic capacities and instincts, it is highly unlikely that communities themselves can manage basic investments (schools, information centers, etc.). The DRC government expects the international community, with its army of NGOs and aid agencies to develop the country. But community buy-in is a foreign ideal that is certainly not shared by government. The government does not care who provides the pump, the bridge, the school or how it gets there – just that it gets done. (It cannot organize or implement such projects on its own--this should be shameful but political elites could care less.) It is the governmental leaders, more than the people, who need new values and perspectives. While working with Congo’s inexperienced and self-serving political class may not be as easy to do as community mobilization and education at the grassroots, it should be part of a transition strategy in countries like the DRC.

On a very different note: the old Zaire/MPR flag is still my favorite, despite its association with tyranny and megalomania. What other national flag can boast a human appendage brandishing a flaming torch? Far more declarative than the usual combination of stars, swaths and stripes.

On a very different note: the old Zaire/MPR flag is still my favorite, despite its association with tyranny and megalomania. What other national flag can boast a human appendage brandishing a flaming torch? Far more declarative than the usual combination of stars, swaths and stripes.[1] One from the previous government (Yerodia Ndombasi), one from each of the main rebel groups (Jean-Pierre Bemba for the Mouvement de Libération du Congo—MLC and Azarias Ruberwa for the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie—RCD-Goma), and one from the unarmed political opposition (Z’Ahidi Ngoma). Long-time political figure, Etienne Tshisekedi, leader of UDPS (Union for Democracy and Social Progress) and former Prime Minister under Mobutu, was excluded.

No comments:

Post a Comment