DDR is the process by which ex-combatants from rebel and government forces are disarmed, demobilized and reintegrated into civilian life. Those who pass certain tests are allowed to remain in the national army, the remaining adults are given a short-term stipend and some vocational training.

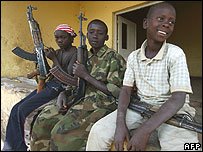

DDR is the process by which ex-combatants from rebel and government forces are disarmed, demobilized and reintegrated into civilian life. Those who pass certain tests are allowed to remain in the national army, the remaining adults are given a short-term stipend and some vocational training.Minors, of whom there were an estimated 30,000 associated with armed groups in the DRC, qualify only for civilian life. They are automatically demobilized and reintegrated because their association with armed groups is prohibited by international humanitarian law and a clutch of related international treaties and conventions specific to the rights of children. The work of de-militarizing their minds and acclimating them to school, village life with their family, the poverty and monotony of the life they left behind, is still an experiment. Programs differ significantly from country to country, as new methods are tried in light of past failures. The children dont get any 'better' at the programs, and are generally very difficult to work with, in addition to being violent.

In 2005 and 2006 I've been working in and evaluating several such programs in Burundi and DR Congo. It has been fascinating, but also enormously frustrating. There is always much to criticize in any aid program. Things rarely go as planned and measuring impact in highly insecure and fluid environments is notoriously difficult.

In 2005 and 2006 I've been working in and evaluating several such programs in Burundi and DR Congo. It has been fascinating, but also enormously frustrating. There is always much to criticize in any aid program. Things rarely go as planned and measuring impact in highly insecure and fluid environments is notoriously difficult.But DDR is unlike any other aid effort because of its close links with human security and its centrality to the pacification of the country itself. It's no exaggeration to say that a poorly executed DDR program adds a new powderkeg to an already volatile situation, and can re-ignite widespread violence when participants decide to withdraw from the program. The consequences of poor performance in other types of aid programs, like emergency nutrition or medical services, do not include returning the country to war. This happened in Liberia: failed DDR programs in the late 1990s meant a return to war. A new

international commitment to bring belligerents back to the negotiating table took much time and money, and only then could another DDR program get

underway.

This week, Amnesty International released its independent investigation into the success of child DDR efforts in DR Congo, called "Children at war, creating hope for the future."

BBC covered the story, highlighting the fact that the "missing 11,000" children are girls "used as sex slaves by military commanders or regarded as dependents of adult fighters." Girls made up 40% of the children taken by armed groups during the war yet the vast majority remain unaccounted for, according to Amnesty. "A lot of them were used more as sex slaves and therefore the combatants are considering them as their possession or their wife," Amnesty researcher Veronique Albert told the BBC.

It is an accurate claim. Girls associated with armed groups--often abducted by force, sometimes joining voluntarily--have proven nearly impossible to access and get released by soldiers and rebels

alike. There are many reasons for this, most of them cultural: the end result is that many girls choose to stay with these men, with whom they now have children. Read Amnesty's press release here.

With the second round of presidential elections approaching on 29 October, I dont think the problems with the DDR program pose a great risk to a peaceful outcome. There is already enough hate speech circulating and private militias

waiting in the wings, to deliver a crippling blow to the country's recovery. Today's report about Kabila's party representatives in London getting assaulted by a mob of Bemba supporters is indicative of the overt tensions around elections.

No comments:

Post a Comment